The opening sequence of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the sixth film in the James Bond series, has Bond saving a glamorous woman from killing herself by drowning on a beach near Estoril at dawn. After some slightly improbable fighting with a couple of villains among fishing boats - one of the villains ends up trapped in fish netting - Bond returns to the Palacio Hotel. He parks his Aston Martin next to the car that belongs to Contessa Teresa ‘Tracy’ di Vicenzo, the woman he has just saved … the scene is set for the beginning of their romance.

The opening sequence of On Her Majesty’s Secret Service, the sixth film in the James Bond series, has Bond saving a glamorous woman from killing herself by drowning on a beach near Estoril at dawn. After some slightly improbable fighting with a couple of villains among fishing boats - one of the villains ends up trapped in fish netting - Bond returns to the Palacio Hotel. He parks his Aston Martin next to the car that belongs to Contessa Teresa ‘Tracy’ di Vicenzo, the woman he has just saved … the scene is set for the beginning of their romance.

During World War II, Portugal was a neutral state. Besides being the point of departure for Jews and others fleeing the Nazi madness to North America, Lisbon was equally an important espionage hub, with agents and double agents tailing each and sometimes meeting openly in the capital’s bars. One of these agents was the Serbian spy and British double agent Dusko Popov … a character who fascinated Ian Fleming when, in 1941, the two men met in Estoril.

After a brief pre-war career in journalism, Fleming was now working for the Naval Intelligence Division, as personal assistant to its director, Rear Admiral John Godfrey. In May 1941, Fleming and Godfrey visited Lisbon together on their way to Washington to promote intelligence cooperation with the Americans. British Intelligence wanted the Americans to create a foreign intelligence agency similar to MI6. In Washington, Godfrey met with the American President, Roosevelt, while Fleming assisted in drafting a charter for the new agency, to be known as the Office of Strategic Services, the forerunner of the CIA.

On the return journey to London, later that summer, Fleming again stopped off in Lisbon, deciding to make his headquarters at the Palacio Hotel in Estoril. Frequented by exiled royalty, the Palacio attracted Fleming because it adjoined the Casino where he could gamble and also had a bar that served excellent cocktails. Like Fleming, Popov was a gambler with a taste for women and drink. Godfrey had asked Fleming to take a look at the dashing double agent’s activities. Fleming had met the man who would later inspire him to create the character of Bond in his series of spy novels.

In the 1930s Fleming had met a woman who was to play a transformative role in his life. Maud Russell was a German Jewess whose parents had settled in England in the 1890s. Her father, Paul Nelke, had made a considerable fortune as a stock broker and Maud herself had married another extremely successful stock broker, Gilbert Russell, a cousin of the Duke of Bedford. Russell’s brother Claud had been the British ambassador to Portugal from 1931 to 1935.

Through Russell, Maud met the political and social élite of the day. Her particular interest, however, was the arts and she befriended many of the leading artists and writers of her time, while building a discerning collection of modern French and British art. Music was equally an important part of Maud’s life and she supported many young musicians.

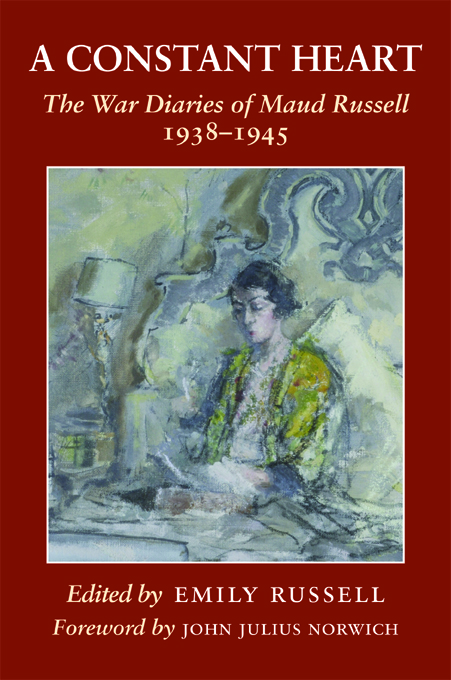

Although Maud was sixteen years Fleming’s senior, the two formed a strong friendship which gradually developed into an intimate relationship. Their friendship is one of the many fascinating threads of a remarkable book that has recently been published by The Dovecot Press: A Constant Heart, The War Diaries of Maud Russell, 1938-1945. The diaries have been edited with great sensitivity by Emily Russell, Maud’s granddaughter, and I recommend them as an impossible-to-put-down read for anyone interested in the major political and military events of the war and in its social history. The cast of characters includes, among many others, the Mountbattens, Duff and Diana Cooper, Lytton Strachey, Kenneth Clarke, Cecil Beaton, Roger Fry and Henri Matisse, who made two drawings of Maud.

It is probable that Gilbert Russell was instrumental in Fleming obtaining his job in the Naval Intelligence Division. Maud writes in her diaries, “he loves his NID better than anything he has ever done, I think, except skiing.” In May 1942, Russell, who had been a long time sufferer from asthma, died. The marriage had been an extremely affectionate one and Maud was completely devastated by her loss.

For the remainder of the war Maud was to be emotionally dependent upon Fleming who had become her confident. Life without Gilbert seemed sad and empty and, in addition, Maud’s two sons were away at war – the elder of the two, Martin, working as Duff Cooper’s personal assistant in the Far East. Maud longed to be useful and make her own contribution to the war effort.

Fleming obtained Maud a job in Naval Intelligence, where she worked unpaid six days a week in Room 17Z beneath the Admiralty building on Horse Guard’s Parade. The pre-war society hostess and patron of the arts was now part of a propaganda liaison unit crafting information to undermine enemy morale. She wrote in the diaries, “he [Fleming] has saved my life, or given me a new one.” At the weekends she would head to Mottisfont Abbey,* the beautiful country house in Hampshire which she and Gilbert had bought before the war. Mottisfont was being used as a home for children re-located from London to avoid bombing and also as a billet for American soldiers. Maud made friends with them all, interested herself in needy villagers and learnt to make cheese, an activity that became a passion.

The war dragged on with its multitude of uncertainties. In December 1938, a few weeks after the Kristallnacht crack down on the Jews, Maud had flown to Cologne to check on her relatives. She arrived on a day on which Jews had been forbidden to go into the street between 8 am and 8 pm and found a notice posted in her hotel bedroom announcing that Jews were forbidden to stay in the hotel. Maud was successful in bringing a number of her relatives over to England, where they began new lives. Some of the family did not, however, wish to leave Germany and most later died in German extermination camps.

Fleming rose rapidly through the ranks of Naval Intelligence eventually becoming responsible for 300 marine commandos. Missions abroad were dangerous and work at home in the Admiralty exacted constant nervous strain. Fleming worked as hard as he drank and smoked and, in the evenings, he would unburden himself to Maud in her London flat or over dinner at Prunier’s. From time to time, he would share his dream of a cottage, somewhere quiet, where after the war he would be able to rest and write.

Maud refused to marry Fleming, although she may have been tempted to. She considered their age gap too important and, when he eventually married Ann Charteris, she gave him her blessing. Maud also give him a gift of £5,000, with which he bought a plot of land in Jamaica and built a house that he named Goldeneye, after a secret operation in which he had participated during the war.

It was here at Goldeneye that Fleming wrote the Bond novels, during two months holiday taken each year. The first of these novels, Casino Royale, was published in 1953. In their correspondence, Fleming had sometimes addressed Maud as ‘M’.

Written with emotional intensity and elegance, these diaries are an engaging read and provide us with a particularly perceptive and moving private account of daily life at a critical moment of British history. Maud Russell was a woman of exceptional intelligence and wide interests and her diary entries are full of humorous observations and humanity.

© James Mayor, 2017

For further information, click on:

A CONSTANT HEART - The War Diaries of Maud Russell 1938-1945

Published by The Dovecote Press

ISBN: 978-0-9929151-8-6

* Mottisfont Abbey (from Wikipedia)

The arrival of Maud and Gilbert Russell in 1934 made Mottisfont the centre of a fashionable artistic and political circle. Maud was a wealthy patron of the arts, and she created a substantial country house where she entertained artists and writers including Ben Nicholson and Ian Fleming. She commissioned some of her artist and designer friends to embellish Mottisfont, always with an eye on its history, which fascinated her. Rex Whistler created the illusion of Gothic architecture in her salon (now known as the Whistler Room), a piece of trompe-l'œil painting that recalls the medieval architecture of the priory. Boris Anrep contributed mosaics both inside and outside the house, including one of an angel featuring Maud’s face – the couple had a long love affair.

Maud Russell gifted the house and grounds to the National Trust in 1957, although continuing to live there until 1972.[2] One of the artists who had visited regularly was Derek Hill, a society portrait painter who had a private passion for landscape painting, and who collected work by his contemporaries. He donated a substantial collection of early 20th-century art to the National Trust to be shown at Mottisfont, in memory of his long friendship with Maud Russell. Today, these works are joined by a changing programme of temporary exhibitions of 20th-century and contemporary art.

__________

The author, James Mayor, is the founder of Grape Discoveries, a wine and culture boutique travel company

See the 'Grape Discoveries' website